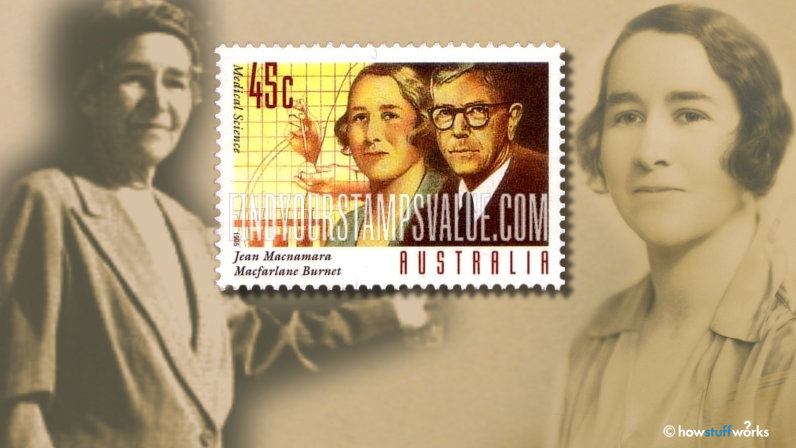

A recent piece about Dame Jean Macnamara DBE (1899-1968) reminds me again of my great debt to her. She was the scientist and physician who, when I was about seven years old, figured out that I had had polio six years earlier.

Jean Macnamara distinguished herself at the University of Melbourne, graduating in 1922 with degrees in both surgery and anatomy. She went on to become a resident medical officer at the Royal Melbourne Hospital and was just 23 when she was appointed resident at the Royal Children’s Hospital in May 1923. It was a critical time as poliomyelitis was sweeping the globe. After leaving the hospital, in 1925, she entered private practice to focus on poliomyelitis patients.

Her research found that that immune serum needed to be used in polio treatment during the pre-paralytic stage. She published and defended her results in both Australian and British journals, though it was a treatment that was never widely administered.

However, it was her discovery in 1931, along with Australian virologist Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet, of more than one strain of the poliovirus that made her reputation. Their finding was one of the first steps toward the eventual discovery of the Salk vaccine.

Macnamara travelled to England and North America on a Rockefeller Fellowship from September 1931 to October 1933, meeting President Franklin D. Roosevelt, himself a victim of polio.

In addition to her keen interest in curing disease, Macnamara sought to alleviate the pain and suffering it left in its wake. She is credited with ordering the first artificial respirator (or ventilator) in Australia. She introduced novel approaches to rehabilitation and splinting damaged limbs, most developed in conversation with patients and her own splint-maker. Macnamara proved to be a tireless advocate for people with disabilities long before it was in vogue.